Three Hungarian Architectural Design Competitions from a Sustainability Perspective – Sustainability criteria in the calls for proposals

In a new three-part series, ABUD’s consultants examine how sustainability should be incorporated into the criteria for architectural design competitions. The current first part discusses the sustainability requirements – or the absence thereof – in the calls, while the second part presents an overview of the evaluations. The third part seeks to identify ideal responses to the sustainability criteria.

News reports have recently revealed that this summer could be the warmest on record in Central Europe. This is concerning in light of the emerging energy crisis, especially given the high cooling energy demand from the growing number of glass-fronted office buildings without external shading. However, the long-term implications of this trend are even more worrying. As a prominent Hungarian sustainability expert noted, this summer may be the hottest of our life so far, but it may also be the coolest for the remainder [1].

With such prospects, it is particularly concerning that Hungarian design competitions continue to address sustainability considerations superficially, that is, superficially honouring them with meaningless buzzwords. Although calls for proposals commonly indicate that the evaluation committee will give priority to an entry for being sustainable, green, climate-friendly, innovative, smart and low-carbon, they rarely specify what the tendering authority means by this. Therefore, contestants tend to interpret these terms as they see fit.

The essence of sustainable development is to fulfil present needs (such as the necessity for new offices) in a way that allows future generations to satisfy their own [2]. Although forecasting future needs is challenging, but it is unlikely that the main concern will be the construction of new offices.

In our series of articles, we explore how sustainability should be taken into account when establishing the criteria for architectural design competitions.

The sustainability requirements – or lack thereof – of the calls are discussed in the current first part of the series, evaluations are summarised in the second, and in the third, we aim to identify the optimal responses to the sustainability criteria.

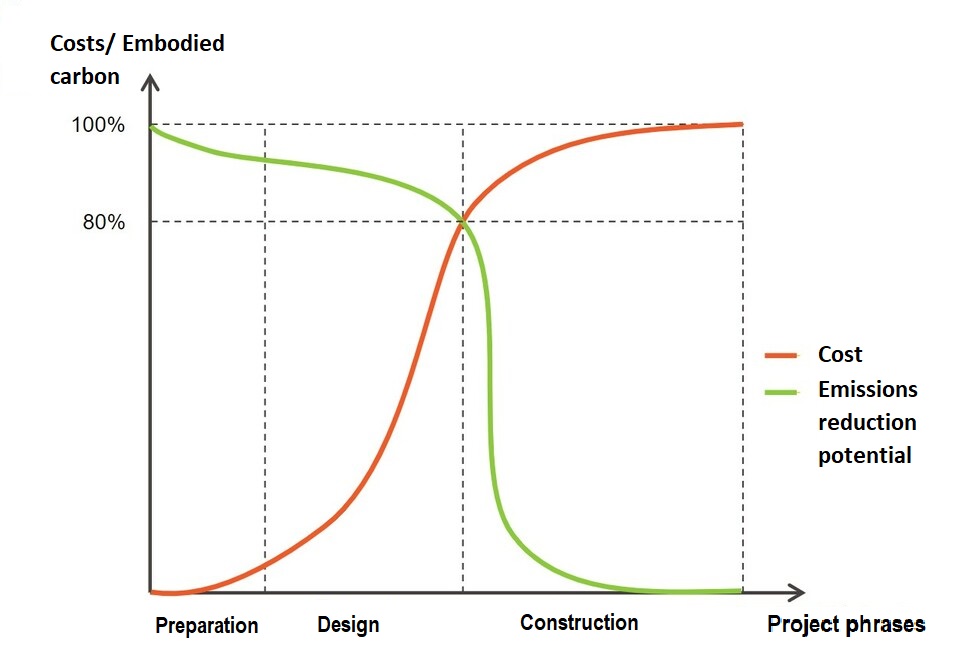

At least ten calls for proposals have been issued in Hungary over the past two years. Given the scale of the projects and their location in natural environments, it would have been crucial to consider sustainability from the outset (e.g., in the case of Matthias Corvinus Collegium [MCC], Keszthely waterfront development, etc.). The most economical and effective way to implement sustainability considerations is at the earliest stage of a project (Figure 1). As we cannot provide an overview of all of the recent large-scale projects, we will focus on the sustainability elements of three recent design competitions. Our familiarity comes from our involvement as sustainability consultants in the respective projects. The competitions in question are the calls for Pázmány Péter Catholic University’s (PPKE) new Budapest campus, the Hungarian Museum of Architecture’s Park (Építészet Ligete) and the reconstruction of Nyugati Railway Station.

Each design competition is a valuable investment that serves the public interests and holds significant national economic importance. Two of them were issued by the Budapest Development Centre (BFK): PPKE and Nyugati Railway Station; while the Hungarian Academy of Arts (MMA) issued the tender to renew the Hungarian Museum of Architecture. PPKE and Nyugati were anonymous, invitation-only design competitions with 12 contestants. the Hungarian Museum of Architecture was an open and anonymous competition with 36 submitted entries. We would like to emphasise that our review of the design competitions and entries is being conducted as independent experts, solely from a sustainability perspective. We do not intend to delve into the architectural solutions or the results of the competitions.

Figure 1: The relationship between grey emissions, costs, and project phases (Original image: Michele, Perera, and Davis [2015])

How is sustainability (not) included in the evaluation criteria?

In order to assess the sustainability aspects, the three calls for proposals, and the associated design programmes and background studies were reviewed. The sets of evaluation criteria for each of the three calls focus primarily on aesthetics (, identity, contemporary architectural language ) and architectural ideas (spirit, symbolism), in addition to functional requirements. Then there is the issue of investment and operating costs, with which all three calls for proposals seem to confuse sustainability. It is undeniable that cost-effectiveness is an important element of sustainability – many green technologies have not yet been able to scale up because of currently low returns. At the same time, a solution may be economically viable in a given market context without being sustainable (e.g., gas boilers).

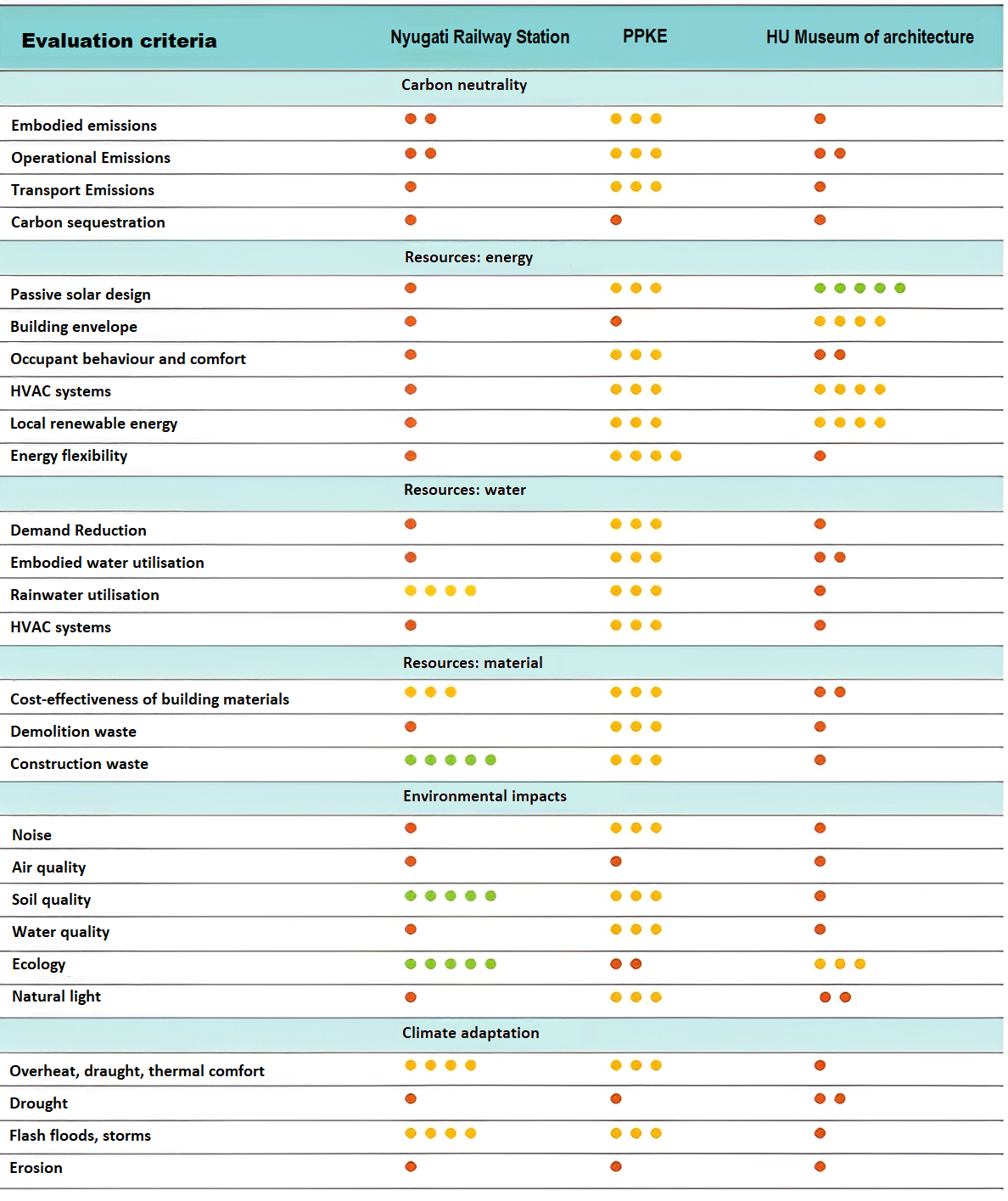

Table 2: The inclusion of sustainability in the criteria of the three calls for proposals. Sorted in ascending order by level of detail: no or inconsistent requirements (1 point), general criteria (2 points), design guidelines/conceptual phase requirements (3 points), required good solutions (4 points), design requirements or indicators (5 points).

Carbon neutrality is important tool for keeping global warming below 1.5 °C and thus ensuring a more liveable future. In essence, it means achieving a balance between the amount of carbon dioxide emitted, and the amount of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere and stored in carbon sinks [3]. In architectural design competitions of this scale, carbon neutrality can be achieved mainly by reducing embodied emissions (e.g., from the production of building materials), operational emissions (e.g., from heating) and emissions from transport, and carbon sequestration (e.g., by creating forests and peatlands), so we looked for these in the calls for proposals. In the case of Nyugati Railway Station, general buzzwords, such as ‘climate protection’, ‘low-impact building materials’ and ‘efficient operation’ appear, but there are no specific requirements or further explanation of how the designer should achieve these. In contrast, the PPKE’s call for proposals sets out more specific requirements for carbon neutrality in the form of BREEAM criteria (e.g., life cycle analysis of the main building structures). However, these only need to be demonstrated at a later design stage (concept design), so they do not constitute a substantive requirement for applicants. Furthermore, the PPKE’s call is not even consistent with the criteria for carbon neutrality. Although it prioritises carbon neutral modes of transport and requires a significant number of bicycle parking spaces, it does not require the reduced number of car parking spaces recommended by BREEAM (less than 160), but instead a minimum allotment of 200 parking spaces, which is even more than the amount required by the Hungarian Building Code (OTÉK). The Hungarian Museum of Architecture sets out general requirements for carbon emissions indirectly: it prioritises passive (i.e., carbon neutral) energy solutions, but does not set out any criteria for building materials and transport. There is no emphasis on carbon absorption, except for an undefined requirement for “as much greenery as possible”.

Building energy is the key area for achieving carbon neutrality. Decisions made early in the design phase can have a major impact on later energy performance, for example passive design solutions (e.g., natural ventilation, buildings optimised for passive solar gain in winter and for shading in summer), consideration of local renewable energy production, and planning for energy management at the building complex level. Of the three architectural design , only PPKE and the Hungarian Museum of Architecture specify requirements for the energy performance of buildings, and both follow different strategies. Again, PPKE follows the BREEAM criteria for the conceptual design phase (e.g., analysis and application of passive solutions and renewable energy sources based on the results ). The jury of the Hungarian Museum of Architecture welcomes the passive use of renewable energy, with particular emphasis on the passive solution for ventilation. They also require a life cycle analysis to be conducted for active energy systems and provide examples of possible energy system designs in a study. The Nyugati call does not set any requirements for building energy.

The country’s water balance is already negative, with more water leaving the country than coming in. The unequal distribution of rainfall as well as longer and drier periods caused by climate change are not helping [4]. It is therefore essential that new investment projects are designed to maximise the use of rainwater. Water management regulations may require the use of rainwater and embodied water (water from sinks and washing machines that can be used to flush toilets after cleaning). The Nyugati Railway Station call is the first to set an open, quantitative indicator that requires as much of the rainfall as possible to be used locally. The Hungarian Museum of Architecture gives preference to embodie water reuse but does not mention rainwater utilisation. The BREEAM-compliant PPKE call for proposals maximises the amount of rainwater run-off from the site, although it does not specifically ask applicants to provide evidence of this.

The role of environmental protection in architectural projects is twofold. On the one hand, a good entry will identify existing and potential negative environmental impacts (e.g., noise, air pollution), and set requirements for remediation and minimisation of further damage. On the other hand, a forward-looking priority investment should not only to cause less damage to the ecosystem, but also to restore previous damage and create new habitats (regenerative approach [5]). Environmental impact criteria are sorely lacking from the requirements of all three design competitions. There are no guidelines for noise protection, air quality, ground pollution and water quality, and only the Nyugati Railway Station’s call requires the remediation of contaminated sites. Habitat protection and urban ecosystem management show a mixed picture. All three calls reward the creation of green spaces. In addition, the Hungarian Museum of Architecture prioritises the promotion of urban ecosystems too – but does not define specific requirements. The most precise in this respect is Nyugati, which calls for the creation of wetlands, large contiguous green spaces, and a specific ecological corridor independent of roads – all integrated into the wider network of urban green spaces. However, Nyugati’s call fails to describe what makes an ecological corridor functional, and what distinguishes it from any other green corridor.

Similarly, there is no requirement for climate adaptation, even though this is the area where design decisions at the tender level are the most critical. Installation, landscaping, use of materials, and green infrastructure will determine what happens in the area during extreme weather conditions that are becoming more frequent due to climate change (think of the overheated deserts of pavement in summer, or rainwater trapped in streets during storms). In a domestic urban context, requirements should be set to address the risks of overheating, potentially dangerous wind tunnels, drought, unexpected and heavy rainfall, and soil erosion. In the case of the PPKE, the BREEAM criteria again address climate adaptation (e.g., flash flooding, indoor temperature comfort, weather resilience of materials), but as before, these are for the concept design phase and do not address all the aspects we propose. Although the Nyugati call for proposals includes some ideas – trees for shade, permeable pavements – there is no systematic consideration of these risks and their translation into concrete requirements. The criteria for the Hungarian Museum of Architecture do not mention climate adaptation at all.

Demonstration of compliance with the sustainability criteria

As can be seen from the above, there are two types of approach to the calls for proposals from a sustainability perspective: either they adopt the criteria of a third-part certification system (PPKE), or they set general criteria in a superficial wording (all three calls). The problem with the former is that the contracting authority does not require proof of compliance with the published BREEAM criteria but makes it as a task for the concept design phase. This is partly understandable, as it is not realistic to expect every applicant to demonstrate compliance with the BREEAM requirements. At the same time, many issues critical to sustainability are decided at the competition stage without having been meaningfully examined (e.g.,maximising passive solar gain in winter, minimising overheating in summer ). On the other hand, the superficial language of the criteria is a disadvantage because it makes it difficult to determine how each applicant can demonstrate compliance.

It is quite telling to examine what kind of drawings, supporting data, and descriptions each call requires to demonstrate the level of sustainability. Each of the three calls requires a chapter in the technical specifications in which the concepts of sustainability and operation must be presented together. In a sense, this is a false association since a poor design may not be operated sustainably at all, or only at very high cost. In another respect, there are no requirements as to what should be included in this chapter, which makes it difficult to compare plans, it facilitates greenwashing (green marketing without real performance) and encourages solutions that are just as superficial as the requirements. Concerning the design panels, only one of the three design competitions, the Nyugati, requires mandatory sustainability design elements, namely the technical infrastructure for green network connectivity and stormwater management.

Beautiful is what is sustainable

Architectural design competitions could be an important means of driving systemic change and of promoting the widespread implementation of sustainability. This is because key sustainability criteria already arise at the design stage. This is particularly true for priority investment projects, which tend to be large-scale and therefore have a higher environmental impact. In many cases, they are built in environments that are more exposed to the effects of climate change (e.g. city centres). Based on the above analysis, some sustainability issues do appear in the calls for proposals, but the superficial design requirements, the postponement of addressing problems to later phases, the lack of systemic strategies, and the under-defined requirements devalue sustainability aspects, while professional considerations remain mainly focused on aesthetics and architectural ideas.

Design competitions do have the potential to drive the entire domestic construction industry towards exemplary green solutions, but to do so, we need to rethink our relationship with the work and aesthetics of architecture. On the brink of a climate crisis, architectural aesthetics are also changing, and a building’s sustainability and architectural style are becoming inseparable.

This piece is the first of a series of articles on the relationship between sustainability and architectural design competitions. In the next article, we will look at what the profession considers to be good or bad in a building, and the extent to which the architectural discourse is about sustainable performance, by examining the judgement the design bids received.

This article was originally published in Hungarian. It was translated by Zoltán Király with the approval of the original authors.

Rebeka Dóra Balázs – Senior Consultant, ABUD – Advanced Building and Urban Design

Viktor Bukovszki – Senior Consultant, ABUD – Advanced Building and Urban Design

[1] Balázs, Zs., „Közép-Európa valaha volt legforróbb nyarának első hetén lehetünk túl, a java még csak most jön,” [We may be through the first week of Central Europe’s hottest summer ever, but the worst is yet to come] Qubit, June 7., 2022, https://qubit.hu/2022/06/07/kozep-europa-valaha-volt-legforrobb-nyaranak-elso-heten-lehetunk-tul-a-java-meg-csak-most-jon.

[2] Brundtland, G.H., “Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future,” (Report: United Nations, 1987).

[3] IPCC. “Annex I: Glossary.” App. In Global Warming of 1.5°C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 541–62, doi:10.1017/9781009157940.008.

[4] Rotárné Szalkai Á., Homolya E., Selmeczi P., „Ivóvízbázisok klíma-sérülékenysége,” [Climatic vulnerability of potable water supplies] Hidrológiai Közlöny 96, no. 1 (2016).

[5] Andreucci M.B., Marvuglia A., Baltov M., Hansen P., (Eds.), Rethinking Sustainability Towards a Regenerative Economy (SpringerLink, 2021)

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.